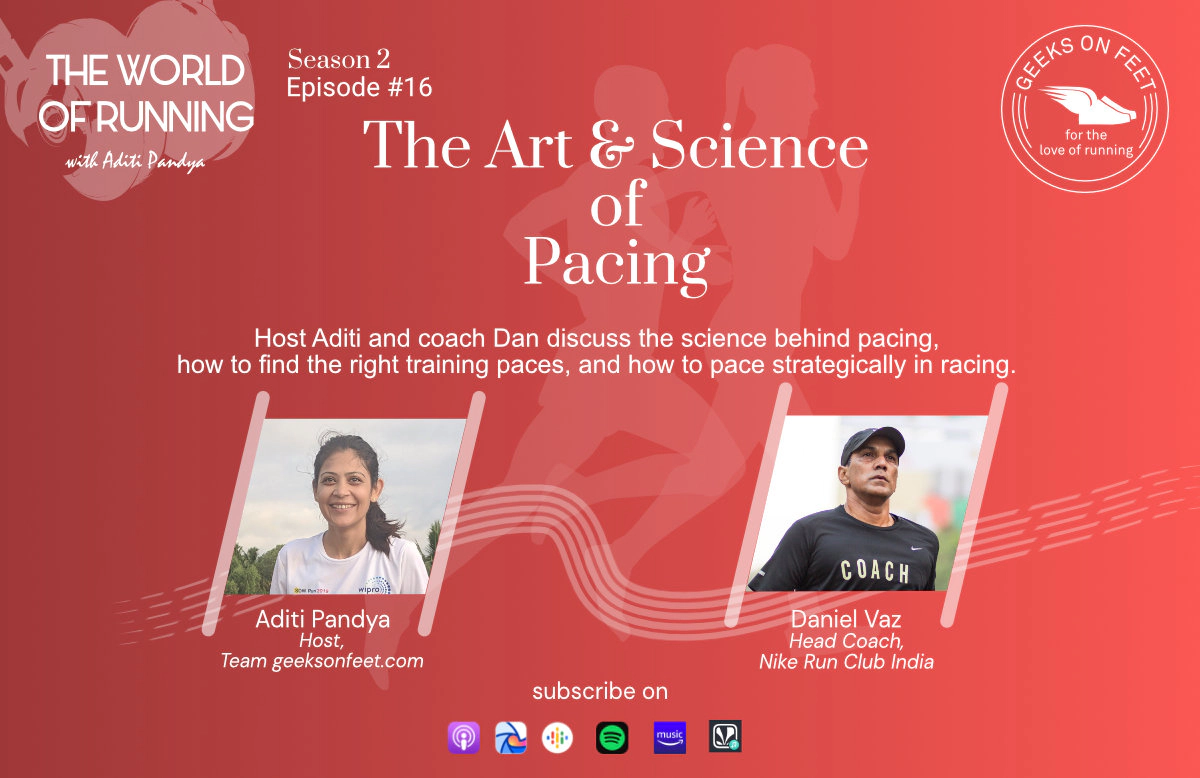

In this episode, host Aditi Pandya discusses the Art and Science of Pacing with Coach Daniel Vaz.

The guest for the episode is Daniel(Dan) Vaz. Daniel is a Certified Strength & Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), from National Strength & Conditioning Association ( NSCA), USA. Apart from this Dan is a certified Ironman coach, has Human Kinetics certification for Running Mechanics and Nutrition for endurance.

Dan has completed 44 full and 2 ultra marathons. He is the head coach of the Nike Run Club, India, since 2008 and part of the Nike Global Coach’s Summit at NYC, the USA in 2015.

Here are a few posts that help you to understand more about Pacing:

For any feedback and collaborations please write to us at [email protected]. Follow us on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook @geeeksonfeet for updates on our recent articles, podcast episodes, and more. You can subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

Please also check the following resources from geeksonfeet.com and runmechanics.in to improve your mobility.

For any feedback and collaborations please write to us at [email protected]. Follow us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook @geeeksonfeet for updates on our recent articles, podcast episodes and more. You can also subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

Aditi ([00:06]):

Welcome to the world of running. I’m your host Aditi Pandya. This is our 16th episode. In this episode, we will be discussing pacing. Pacing refers to the speed at which a runner runs. Pacing becomes important as it ensures runners have enough energy for the entire race, especially for longer distances. There are different strategies to pace for various distances example, one paces with feel, it is also known as Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE). Pacing using GPS watches, or breathing, and there are also workouts to improve pacing awareness.

Before we go ahead with today’s podcast, I have a request for all our listeners. If you like this podcast, and know of someone who’s getting into running, please share a podcast link with them.

Our guest for today’s episode is Daniel Vaz. He’s a certified strength and conditioning specialist from National Strength and Conditioning Association(NSCA) USA. Apart from this, Dan is a certified Ironman Coach and Human Kinetics Certification for Running Mechanics. Dan has completed 44 full marathons and two ultra marathons. He is the head coach for Nike Run Club, India since 2008. And part of Nike global coachs' summit at New York in 2015.

Aditi ([01:38]):

Hi Dan, welcome to our podcast and thank you for accepting our invite.

Dan ([01:43]):

Hello. Thank you. It’s my pleasure.

Aditi ([01:45]):

So Dan, I was reading about you and all the accolades that comes along with your name and that’s the reason we had a special interest to invite you for this particular podcast. We all say that there is art and science about pacing, right? It is not about how much speed you can do, but it’s about how much you can keep and endure that speed. Right? So, pacing includes aerobic and anaerobic energy systems, right? So the first topic I want to talk about, is identifying training paces. And this generally is determined by heart rate and this will be different for various runners. And so my first question goes to you as how can runners identify their running goals and plan their macro cycle.

Dan ([02:35]):

So what’s important is for people to first identify the distance that they plan to race. And, it, if you are a beginner as compared to, if you are a runner who is seasoned, the, the identification of your pace will be different. So for a beginner, the intent is probably to only finish the race and there is no identification of a goal race pace, but for an advanced runner or for a seasoned runner, there is likely to be a goal race pace. So talking first about the beginner, if you’re doing, let’s say a 10K or a half marathon, the intent is, largely to finish the race because you do not have the ability to identify what the different paces are and what your effort level feels like. So, the intent is to complete the distance and therefore in training, you would work with mainly what we talk as the conversational pace or easy pace, which is a pace during which you are able to speak to another runner alongside, or even if you don’t have another runner alongside you are able to, let’s say, recite a poem to yourself.

Dan ([03:56]):

That’s only one way of identifying that you are at an easy effort level, and this is the pace that you will maintain in all the distances that you have in your training schedule, whether it’s starting with, 5K to an 8K to a 10K. And if you are making the transition to a half marathon, you’d probably go to a 15K, 16K, or 18K. All of these distances in training, you are going to work with, just your easy pace. Now coming to identification of goal pace for, let’s say a season runner, you would first need to find out what has been your paces for, distances lower than the goal race. So if you 10K race coming up, a, what has been your, you know, 5K race base and or what has been your 10 K pace in a previous attempt, you would use this and the way to attempt or fix a goal for that pace. If you have a 10, I’d say the likelihood of you doing anything better than 10 to 12 seconds, a per kilometer is remote.

Dan ([05:11]):

So you have to target something like around, let’s say seven to eight seconds per kilometer improvement. And this improvement you can hope to get in, let’s say a 12 to 16 week cycle of training. You use this as the base, and then you schedule your training plan accordingly. And let’s say, if your pace, as an example, since we are talking about figures is six minutes per kilometer for a 10K that you have done earlier. And if you want to do, let’s say seven to eight seconds per kilometer faster, then it would be 5:53, right? So you take 5:53 as your goal race pace and use it in your training to identify whether you can hold this pace for a majority of the distance that you are planning, which means that one of the workouts that you would use is to find out race pace in the workout.

Dan ([06:13]):

So typically you would attempt, let’s say 5K at the race pace of 5:53 and do something before that at easy pace, to warm up, which means, let’s say you do 2K at easy pace and another 5K at your target race pace, which in this case, the example is 5:53. If you’re able to hold this without a problem, you make then the transition to using 7K or 8K. By 8K you know, more or less whether in training, you can hold this pace and mind you, this would normally happen in the final five weeks before your race, because till then you would build up your, ability to speed and endurance to get this kind of a target race pace in place. So this is just one of the workouts, as I said. I also have to explain to you that if you were to use your 5K, time to extrapolate and find out what could be your 10K time by and large, the guideline is that if you have a 5K time then the, the pace for the 10K is around 10 to 12 seconds slower.

Dan ([07:26]):

Okay. So if your 5k, if your 5k is, let’s say at 25 minutes, which means it’s a five minutes per kilometer pace, you would end up doing 5:12 or 5:10 for 10K slower, right! That means you have to add the 10 to 12 seconds. So this becomes your target pace. When it comes to other training basis, we could talk about it as we develop, further on this question as to what are the range of other paces that you need to mix within your training plan. But the first thing I wanted to identify and let people know is that race pace is, this is a way to identify, like I explained to you. And the second is to incorporate it in your runs so that you can find out for yourself whether your goal is achievable or not. And that gets seen in the final five weeks before actual race, right?

Dan ([08:21]):

So the macrocycle then becomes, as I said, 12 to 16 weeks because that’s the kind of timeframe within which you can hope to get what we call an exercise physiology as adaptations. You know, you cannot get adaptations in four weeks or six weeks. You need 12 to 16 weeks to get adaptations. In the case of a half marathon, the macrocycle could be a little longer right up to 20 weeks. And of course in a full marathon, you can work with maybe 24 to 26 weeks because the race itself, the full marathon has a lot of, you know, uncertainties in it. And you need to work quite a lot in order to get rid of those uncertainties. So you need more time maybe around 24 to 26 weeks if you want to identify a personal best. So to say, when we say a goal race pace, we are talking about something better than what you were doing earlier, which becomes a personal best. Yeah.

Aditi ([09:21]):

So this is very helpful, Dan. So just tell you something about myself. I’m planning to do a 10K, if TCS 10K happens. Right. And I just finished my 5K. So I’m, I was just calculating when you spoke about how can I time my pace? So thank you. So Dan, I want to actually now switch our focus on endurance, right? And when I talk about endurance, they are the easy, long runs. And so Dan, when I talk about rate of perceived exertion, the scale can be between one to 10 and basically one and two values will be basically for a runner to who can talk to the fellow runner. And 60 to 70% of the runs should be at this endurance pace. So my question is how do identify one’s easy run pace, while training, You could do that with either heart rate because, heart rate can come in useful when you want to work out easy pace running or endurance or long run pace as we call it. You could work with a heart rate of anywhere between 65%, two 75% of your max heart rate. And this is a good target range for any person who, of course, the requirement is that you need to know what is your heart rate max? And I must state at this point of time to the listeners that they should identify the max heart rate, not from 220 minus your age, because that’s an empirical formula developed for a certain statistical population. And it has been found that it’s true for only 60% of the runners or the population and the balance 40 could be either below it or above it.

Dan ([11:12]):

So the right way first to find out your max heart rate is work with a 400 meter track where you run the 400 meters, one loop of 400 meters at your best effort level, then you rest for just one minute. Okay? Which means that meanwhile, you are recording your heart rate, right during that 400 meter interval. So you rest for one minute, you hit a second loop at your best effort level. Again, you are recording your heart rate, you rest for one more minute, and then you hit the 400 meter loop a third time. And in these three best effort level, 400 meter loops, you will, and you are likely to hit your max heart rate. And that should be the value that you should choose as your max heart rate and work with that value to identify what are your, heart rates for other training paces or other you know, goals in terms of whether it’s lactate threshold or V02 max, which we can talk about. And yeah, I must state that a heart rate monitor, which is a chest strap, is the best thing to use because any of the wrist based optical methods sometimes can be erroneous. So that’s using the heart rate method, but like you mentioned, there is a one to 10 scale. And usually in the one to two rating of that scale, you are able to speak about two to three sentences we state, you know, when you are at rating of RP of one to two, you can speak two to three sentences, which really means that you are having a comfortable conversation. This is the effort level which runners should strive for when they want to talk about their easy pace and their long run pace and or their endurance pace. So bulk of your running is meant to be aerobic where you are accumulating just you know, time on your feet or mileage as we call it. And this has to be done at an aerobic level. Aerobic level is when you are comfortable, you are so to say burning more fat than carbohydrate, and that really allows you to stay on your feet for a long time. So runners should use this guideline either using the effort level or heart rate, the way I explained it, and you should be fine.

Aditi ([13:35]):

Great. So that is clear, Dan, and I want to ask you that how can runners work on improving their future goal or marathon pace?

Dan ([13:45]):

So here I have, I would like to differentiate between you know marathon pace as in the 42 kilometer full marathon pace and the other races, which can be the 10K or the half marathon. Now, as I said, first, you identify the goal race pace, which we have already covered, right? Whether it’s for the marathon or whether it’s for a 10K. So I actually explained to you how to extrapolate from 5K, to a 10K by saying that you should you know, add 10 to 12 seconds to your pace so you are slower. A further 10 to 12 seconds. When you add, you will reach what we call as your 10 mile pace, which is approximately your 16K pace. Okay. A further 10 seconds. If you add, you will each half marathon pace, all right. And another 10 to 12 seconds you add, you would reach your full marathon pace, but it’s easier said than done to achieve the full marathon pace. So I’ll treat that separately. Okay. So that means you had a 5K time trial. I showed you what can be your 10K race pace. I showed you what can be your 10 mile race pace, right? Plus 10 seconds, plus 10 seconds, plus 10 or 12 seconds up to the half marathon. All right. So you use this, and then you use training schedule in which you are building mileage using the RP of one to two and 60 to 70% of your total time in the week where you are investing in running. So it depends on how much time you’re investing, whether you are investing four days a week or six days a week. So it depends on how you know, adapt a runner you are. It’s not possible to prescribe that you should run six days a week, or you should run five days a week. It all depends on where you are at the current point of time. If you’ve been training for four days in a week, stick to four days in a week and work on progressive you know, improvements or additions to that so that you don’t get injured. Once you work with this four days or five days in a week, you know how many hours you’re investing, let’s say you’re investing let’s take the example of four days in a week. So three days are midweek and one day is the weekend. So the three midweek days you are, let’s say investing about an hour to 75 minutes of running, because that’s all you can afford to do. If you are a professional and you need to go to work and things like that, it’s the weekend , when you are free to invest a lot more time in your long runs, which can be anywhere from two hours to three hours, as long as you are up to the half marathon goal. If you are at the full marathon goal, maybe you need to invest four hours or four and a half hours closer to your, you know, goal race. So to say, and out of this, as we stated, these three plus two, six or seven hours, 60% of this, you have to invest in aerobic runs, right? So that’s about 3.6 to 4 hours, which means balance time of two hours. You need to invest in speed workouts. Now speed workouts can be you know, at lactate threshold, which can be your tempo runs. They can be at V02 max pace or effort level. And they can be even beyond V02, max effort level, which we can talk about as we go along, which are called repetitions.

Dan ([17:16]):

So you have lactate threshold runs, you have intervals, which are largely Vo2 max. And you have what are called as repetitions. These are definitions, which many authors use I’m using the definition given by Jack Daniels in his book. So there is long tempo runs, short tempo runs, intervals, and there is repetitions and you incorporate all this in a training schedule and hitting all these paces means you are targeting different metabolic states in your body and getting different adaptations in terms of whether you are increasing the mitochondria in your muscles, whether it is increasing the cardiac output by way of the V02 max going up, or whether you are able to handle blood lactate, you know, effectively, even if it comes into your bloodstream. So this is how you would create adaptations during that macro cycle, which I spoke about 16 weeks, 20 weeks, 24 weeks. And you will at the two weeks or three weeks before hit your target race pace. If you’ve got all the schedule right in place,

Aditi ([18:27]):

Looking at the new of the hour and keeping comfort and safety in mind, RunMechanics have launched the online option for running form analysis, which is simple and can be done at your convenience, For online running form analysis, runners need a smartphone and natural light. Runners can opt to run on treadmill or a road or a track. This can be done in three simple steps, log in and create your profile, record your run, and upload your video. To know more about online running form analysis, visit www.runmechanics.in.

Aditi ([19:09]):

Somewhere, you spoke about VO2 max, tempo, repetition, speed intervals. And I want to take one by one, all of that. So we talk about tempo, which is also known as lactic threshold, and these are faster than a marathon pace and slower than intervals. And the reason why we tell them as lactic threshold is because our body releases lactic acid, which is a chemical byproduct of anaerobic respiration. Now also if we have a better lactic threshold, it helps us to run better aerobic state of running. Right? So my next question is how do identify a runner’s current lactate threshold pace?

Dan ([19:58]):

The first thing to do is understand what is lactate threshold from a technical standpoint? Well, the, the body has the ability to be able to metabolize carbohydrate or glycogen which is its storage form in two ways. One is, you know, the oxygen dependent pathway as we call it. And the other is the oxygen independent pathway. So what are these pathways? It is just that when you are running at an easy pace, right, the amount of oxygen that you breathe in, your blood takes it in up to the cellular level. And it can be utilized to metabolized carbohydrate into their byproducts, the ultimate byproducts of carbon dioxide and water. So this is what one would talk as complete combustion from an engineering standpoint, right? It’s very clear if carbohydrate is burnt or metabolized to carbon dioxide and water, it would need an adequate amount of oxygen.

Dan ([21:05]):

Now, when would oxygen be adequate? Oxygen becomes adequate when your pace is reasonable or slow or easy, because it is only at such point of time that the amount of oxygen that can be carried by your blood to the muscle cells is going to be made available for this metabolism to take place. As against this, let’s assume that from easy pace, you start increasing your pace gradually. The moment you start increasing your pace gradually, there is a demand for more energy, right? So if there is a demand for more energy, the metabolism of carbohydrate starts increasing. Now at the same time, the amount of oxygen that’s coming in tends to be inadequate. If it is inadequate, then the body ends up creating an intermediate compound instead of carbondioxide and water, it creates an intermediate compound called pyro weight. And this pyro weight then disassociates into blood lactate, or as we call it lactic acid.

Dan ([22:14]):

Now lactic acid is produced under what conditions, a, when your pace is higher than your easy pace and hard enough, and b when there is inadequate oxygen available for metabolism. All right? So this is technically, what is blood lactate, how it enters your bloodstream. Now, when blood lactate enters your bloodstream, we say that lactate is produced and the body has a way by which it is also cleared. So there is a production, and there is an elimination of blood lactate. Now, when the two match you are fine, which means that blood lactate does not accumulate in the bloodstream, but if the amount of production is higher than the rate at which you can extract it, yeah. There will be a result in blood lactate up in your blood. Correct. So it is this increase in blood lactate, which tends to affect runners and slow them down, or cause them to get pain in their calves or in their lower extremities, and ultimately, if your pace is substantially high, you will come to a grinding halt. Threshold is the point at which the production and the elimination are just about not matching. Okay. So as an example, you know, blood lactate is measured in millimoles per liter. So let’s say as an example, that at the point at which the blood lactate produced matches the blood lactate eliminated, and the value is four minimoles per liter in your blood. The moment it goes to 4.5, 4.8, you say that there is blood lactate just about starting to get accumulated in your bloodstream, right? So when it just about starts getting accumulated, going from four, as an example, a numerical example, only to 4.5, you know, that you have reached the threshold at which blood lactate starts creeping up. This is called the threshold, where the blood lactate just about starts creeping up.

Dan ([24:28]):

When it starts creeping up, if you keep on running faster, it’ll go to 4.8, it’ll go to five. It may go to 5.2, and at something like 5.5, it starts shooting up exponentially or really climbing. Okay. So there are these two points. One is when it just about starts creeping up, it’s called the lactate threshold. And when it starts shooting up exponentially, we call it onset of blood lactate accumulation, or OBLA, as it is called. So now, how do you identify such technicalities in a practical way? By the way, I must tell your listeners and the runners that lactate threshold or anaerobic threshold, or, you know, maximum lactate steady state, these are so many definitions about 20, 25 definitions. It is mind boggling for any runner to be able to figure out what all these mean. And most you know, exercise physiologists have not come to an agreement as to what is that one unifying you know, definition.

Dan (25:38):

There is one methodology which is made available, and that is called the 30 minute run. And I must tell you runners that they should utilize this 30 minute run in order to be able to identify their lactate threshold pace. Now, we are very clear that it’s the pace. This is the pace which you can hold for 30 minutes. Okay, I’m going to repeat my sentence. This is the pace you can hold for 30 minutes and, and not more. At the end of 30 minutes, you are well and truly thoroughly exhausted, and you cannot hold that pace any longer. If I’ve made you run for 33 minutes, your pace will drop. Naturally, this kind of a 30 minute test comes only through trial and error because not everyone can get it right in the first instance. So what is the methodology given to you to execute this 30 minute test is to divide it into 10 minutes and 20 minutes. ):

So in the first 10 minutes, you start running and finding out that pace, which you feel I can hold for 30 minutes, in the first 10 minutes, you find that pace, all right, having zeroed in on that, so-called pace you then hold it for the next 20 minutes. If you can, if you got it wrong, the test goes wrong. Okay. If you slow down in the 20 minutes, it means you really got it wrong, which means you have to repeat the test after another three or four days, because you need to be well rested for this test. Okay? You identify your average heart rate. In the first 10 minutes, you identify your average heart rate in the next 20 minutes. They should be more or less close to each other. You add them and you divide by two, which means you really take the average of the whole thing.

Dan ([27:27]):

Okay? And your lactate threshold pace is nothing but the average of the total 30 minutes that you were running. So once you know this, this pace, which is for 30 minutes, you can utilize this pace to either run repeats, which are five, 10 minutes each. And to be done several times, or let’s assume as a numerical example. So that I’m very clear about what I’m stating. Let’s assume that the lactate threshold pace is six minutes per kilometer. This is the pace you able to hold for 30 minutes and not more. Now you can utilize 5 50 or 5 45, which means it’s faster. Or you can utilize 6 12, 6 15, or 6 20, which is slower, right? So you need to now work in your training with faster than lactate threshold and slower than lactate threshold. So what happens is if you use faster than lactate threshold, naturally, you need to run in smaller segments because 6 00 was the pace you could hold for 30 minutes, right?

Dan ([28:42]):

If you work with 5 50 or 5 45, naturaly you’re not going to be running long. You’ll run five minutes, take a rest, run another five minutes, take a rest, run another five minutes, take a rest. You may do about say four or five such repeats. Now, what is the rest period that you have to take when you work in this manner? Now, Jack Daniels has given up nice guideline and it is true and can be utilized by all runners. The rest period is a ratio of 5:1, which means that if you run for five minutes, take a one minute rest. If you run for 10 minutes, take a two minute rest. So your, your training, your body to handle blood lactate accumulation, because as the number of repeats, go up the amount of blood lactate accumulated also goes up. So training your body to handle blood lactate.

Dan ([29:35]):

When you use slower than the 30-minute pace, which is the 6 00 minute pace, and you now decide that you’ll run at 6 12, you can run for longer. You can maybe do 20 minutes into two, you know, so 20 minutes, again, you can take, according to, Jack Daniels, the moment you are at slower than blood lactate, you can take a 10 is to one ratio, which means every 10 minutes is one minute. So if you were running for 20 minutes, you would take two minute rest. So if you did two times 20 minutes, that is a total work period of 40 minutes. You would need a two minute rest between these two intervals. Okay. So 20 minutes at 6 12 pace, 2 minutes rest 20 minutes at 6 12, 2 minutes rest.

Aditi ([30:21]):

Sure. So Dan, my next question was about ideal duration of runs and the number of repeats. But I think that you have already covered it in, in your previous answer. So, Dan, I would like to talk about somewhere, we mentioned about Vo2 and Vo2 max intervals are also higher than the lactic threshold, and they are the fast sections, which we alternate with relatively small recovery periods and which are also equal to the duration of fast sections. Right? So what is the difference between lactate threshold and Vo2 max intervals?

Dan ([30:59]):

Vo2 max is your maximum effortly level when you run. Okay. If I were to put you on a treadmill and I were to increase the speed in segments every two minutes. So to say, then you would end up progressively getting tired and you know, your heart rate would go up and at some point of time you would end giving up. Right? So Vo2 max is a test in which you are delivering the maximum amount of oxygen to your muscle cells at the maximum effort level. So if I were to put you on a treadmill and start the treadmill at easy pace, and every two minutes, if I were to increase the speed in segments, at some point of time, your heart rate would go up and reach its max, right? And if at this point of time, I had an apparatus which could measure the amount of oxygen that you’re taking in, as well as the blood lactate, by taking blood samples from your finger, I would be able to draw a graph.

Dan ([32:08]):

The graph would be that the heart rate would climb. And at some point of time it would level out because that’s the max heart rate, right? It’s so also the amount of oxygen that you consume would rise and it would reach a certain maximum level. So Vo2 max means just that it’s the maximum amount of oxygen that is consumed at the cellular level, when your effort level is the maximum. So this is a test which is done in a laboratory and it gives you the amount of oxygen, that is consumed at your cellular level. And it naturally, because it is Vo2 max, your heart rate is max. Okay. So in training, if you were to use, utilized heart rate as a method for Vo2 max kind of runs, you have to use a heart rate, which is 95 to 98% of your max effort.

Dan ([33:05]):

Naturally you can never run at your max effort. It’s not good to run at your max effort. So utilize 95% to 98% of your max heart rate, which I showed you, how you should calculate and use that in your training. So this is the difference. The lactate threshold is pertaining to the amount of blood lactate that accumulates it is naturally at a heart rate, which is much lower than the Vo2 max, how much lower? Well, the range is between 82% to 92% of max heart rate. 92% is what the elite runners, the Ethiopians and Kenyans reach. And when it comes to Vo2 max, it is always at 95 to 98% of your heart rate max. So this is the differentiator between the two. And this is how you would then utilize Vo2 max in your intervals. So intervals here again, if we take what Jack Daniels gives you as a guideline, the ratio is 1:1, and you must make sure that your intervals are short because now you are running at max heart rate and you cannot afford to think that you can run for five minutes or six minutes or seven minutes.

Dan ([34:16]):

Typically intervals are run at two minutes, half minutes, three minutes, three and a half minutes or four minutes. All right, this is how intervals are run. And the rest period is equal to the work period. So if you run two minutes at a heart rate of 95 to 98% of max, the rest period is two minutes. If you run three minutes at Vo2 max pace, the rest period is three minutes because the ratio is 1:1. So this is how you can incorporate either time based intervals, or you can incorporate distance based intervals provided you, keep in mind that you should not be running at more than four minutes at a time at Vo2 max, because it is very stressful to the body, and it is going to create a lot of fatigue. So you may not be able to do several intervals if you’re running the intervals at a distance or time, which is too high.

Dan ([35:15]):

So if you work with 200 meters, 300 meters, 400 meters or 600 meters, depending on what kind of a runner you, you are in terms of your ability provided you cover these distances between two minutes to four minutes, you can utilize them to run intervals and the total number of intervals that you should be running, because that’s also important for you should total about 20 minutes of work period. So if let’s say four minutes, was your interval, how many intervals would you run to make it 20, 5 of them? oIf you were, if you were to utilize two minute intervals, you can run up to 10 intervals to make it 20. All right. So this is how you utilize the difference between lactate threshold and Vo2 max.

Aditi ([36:01]):

So Dan, you desribed the speed intervals very smoothly here. Just one question I have is when should a runner introduce short intervals in their training,

Dan ([36:14]):

Short intervals are utilized large when we talk about improving running economy or trying to get your fast twitch muscle fibers as we call them, muscle fibers which you generally do not use, but they’re used largely in sprint, but they come into use for endurance runners at a stage when they’re giving the finishing kick to let’s say a 10K or a 5K. So these are points at which you utilize your fast twitch muscles, which are type 2B, just as a technical example, though, we will not go into those details. Let’s you have slow twitch intervals, which are endurance based and fast twitch intervals which give you more of power and faster running speed. Now you utilize this kind of a domain as we call it. When you want to improve your running economy, running economy is the efficiency at which you run. All right. It means that when you expend energy in metabolism, most of the energy should go into propelling you forward.

Dan ([37:22]):

An example is, let’s say a car. So if you are running the car in an efficient manner, the amount of patrol it’ll use is going to be minimal or efficient. If I were to deflate the tires of this car, naturally it would run inefficiently, right? So deflating the tires is an example of runners who waste energy when running, how do they waste energy? A classic example is a runner whose upper torso will rotate. You’ve seen runners who swing from left to right left to right, and their arms move across their a body, right? This is called wasting energy. And this is inefficient, running, running economies, low in such runners. So when we incorporate short, fast intervals, we improve what is called as running economy.

Dan ([38:13]):

Ultimately it means that the runner will end up utilizing less of carbohydrate for that particular race, which comes in great use when you are running a full marathon, because, you know, conserving carbohydrate is a very important aspect of running a full marathon. So when you utilize these short intervals, you have to work with rest periods, which are two to four times the work period, which means that if you’re utilizing one minute of short interval, two minutes to four minutes is the rest period. And that’s the kind of rest you need to recover from each interval. And these intervals have to be short enough to make sure that your body is not entirely going into fatigue. That’s all

Aditi ([38:57]):

Understood. So Dan, this is insightful and we’ve covered all the components of pacing. And now we, I want to talk about how we strategize pacing and various races will have different, different strategies. So generally there is a common that belief that we should end, and there is a desire that we should end with negative splits. However, I’ve observed that for longer races, like a marathon, negative splits are generally not achieved because we did an analysis of TMM 2020 and 96% of runners had positive splits. So my question to you is what should be the strategy of pacing for shorter versus longer distances?

Dan ([39:45]):

So in shorter distances, it is possible to get negative splits because you know, you are dependent upon everything that you did in training and the kind of pace that you were able to use as your goal race pace. It can come out true on race day for shorter distances as against the full marathon. Why do I say this? Because in the full marathon, there are a lot of things that go wrong for a runner. And significant out of that is the amount of carbohydrate that is stored in the body. So everyone, right from the recreational runner to the elite runner ends up depleting their carbohydrate stores. And for the last, approximately 10 to six kilometers of the full marathon race, you are running on depleted carbohydrate stores. And this is when your pace drops. So in negative splits, the second half of your race is faster than the first half of your race, which really means that in a full marathon, why you get these 96% of runners having positive splits is, they cannot help it.

Dan ([40:58]):

In the full marathon, you are likely to slow down in the last 10 kilometers to six kilometers. There is no two ways about it. All right, unless, unless you are one of those 4% runners who has got their strategy perfect, in terms of how much of carbohydrate, they had externally ake in terms of gels and how much they had practiced this pace in their training. So it is inevitable that you will slow down in the full marathon and therefore you will get a positive split. The second half will always be longer than the first half. In order to get a negative split in a full marathon, a, you have to put in all the hard work in terms of the mileage, your speed training, and most of all your race based training. So in all your long runs, which are between 30 kilometers to 36 kilometers, you have to be able to hold that race pace without any fatigue. And in all these runs of 30 to 36 kilometers, you have to also practice taking in your external carbohydrates, in terms of gels or electrolyte or whatever it is that works for you, whether it’s banana, dates, etc. So you are feeding your body to make sure that in the last 10 kilometers to six kilometers, you do not get substantially depleted and you are able to dig deep and hold your pace, or even faster than it in the last 10 kilometers. Yes, it’s possible. There are many runners who can do this and they do it because they’ve got everything right. The training has been right. They’ve worked very hard with their race pace. They’ve got their nutritional intake and the timing, correct. And that’s how you can get a negative split. Otherwise you have to work with positive split.

Dan ([42:48]):

But in 5k, 10K and half marathon, you do not deplete your carbohydrate stores. You have ample carbohydrate stores, still remaining in the half marathon to accept for those recreational slow runners who finish in more than two and a half hours, then yes, you can also deplete your carbohydrate stores in the half marathon. But for the most of the runners who are finishing in less than two hours, you don’t deplete your carbohydrate stores, and it is possible for you to work with negative splits provided you have worked in training to find out what is that pace that you can hold for the entire duration of the race without without dropping the pace. Important thing is also taken into account the weather. For example, in the Mumbai marathon, you start with colder weather, and then you end with warm weather. Again, naturally when the weather is warmer, you will slow down. So many things go wrong in a race like the Mumbai Marathon, in terms of the weather, in terms of the terrain, the, the Peddar Road hill comes towards the fag end of the race so naturally you are likely to slow down and it’s not surprising naturally that 96% of the runners get positive splits there.

Aditi ([44:04]):

Understood. So Dan, with this, I come to the last question and you answered it partially. That is what are the parameters that need to be considered when deciding the race pace.

Dan ([44:19]):

So the first thing is to take into consideration the weather, because this is the most significant aspect. When you decide on a race pace, you also have to decide on where you are going to race, which is why a lot of runners end up choosing the Berlin marathon or the London marathon, because a, it is cooler weather than you would get in India because we are talking about runners in India, right? So cooler weather than you would get in India. The second aspect is the terrain. If you have too many inclines or declines in the marathon or your race, you would end up creating fatigue in your legs, even if it’s declined, because declines can end up creating a lot of fatigue in your thighs, which we call it eccentric kind of forces on your thighs.

Dan ([45:14]):

So inclines and declines are going to also cause problems in your pacing and time of the day is largely a function of both the weather, as well as how your overall wellness quotient is. If you are a kind of a runner who runs better in the mornings as compared to in the evenings, it can change things, but the two significant aspects are the weather and the terrain. So choose a race pace, which is going to be based on the temperature of the day for that race and also the terrain. Without these, you cannot target a kind of a goal race pace. Once you have targeted the goal race pace, you need to start practicing in your training using these two parameters. For example, if you were to choose, let’s say as an extreme example, the Satara hill marathon. Now that’s, that’s a long incline followed by a long decline.

Dan ([46:12]):

And in such a case, if you targeted just the Satara marathon and your time for it, you would need to train using hills for that kind of a race. So always simulate your race conditions in training., if you have a target time. If you do not have a target time, it’s a different matter, but you have to simulate your race conditions and training. So also for the weather, one of the things I can tell you is that runners who live in the north of India and who train for the Mumbai marathon, they end up really running in cold weather. Whereas when they come to Bombay (Mumbai) for the Mumbai marathon, they are running in warm weather. So how do you train for it? The only way to train for it is to wear multiple layers of clothing is what I tell my runners. Yeah, you wear two sweatshirts in order to create a core temperature, which is going to be high enough to simulate Mumbai conditions. Because outside weather temperature is in the region of 12, 14, 16 in or even 5 degrees, if you are running in, Ludhiana for example. So how do you simulate Mumbai weather conditions is to wear multiple layers of clothing in your long runs so that you sweat or create a cold temperature, which is higher. So that’s how you can end up training and targeting your goal race pace and achieving it in training.

Aditi ([47:39]):

Understood. So Dan, with this week come to the end of our episode, and I must say I thoroughly enjoyed talking to you and personally, I feel I’m gonna benefit with this conversation, and I hope all the other listeners benefit from this conversation with you. And thank you.

Dan ([47:58]):

Thank you. It’s my pleasure. And thank you for giving me the opportunity.

Aditi ([48:03]):

I would like to thank all our listeners. And if you like this episode and would like to know more on the world of running, please subscribe to our channel. And if you know of someone who is starting their journey into fitness and running, do share a podcast link with them. I would like to thank my friend Aravind for editing sound recording and taking care of the postproduction for this podcast. If you have any suggestions on improving the content of the show or topics you would like us to cover, please share it by emailing us at [email protected]. We generate running content for those seeking technical assistance to training, which is available in our show notes. Or you can also reach us through Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.